Typography

by Casey Reas and Ben Fry

This tutorial is the Typography chapter from Processing: A Programming Handbook for Visual Designers and Artists, Second Edition, published by MIT Press. © 2014 MIT Press. If you see any errors or have comments, please let us know.

The evolution of typographic reproduction and display technologies has and continues to impact human culture. Early printing techniques developed by Johannes Gutenberg in fifteenth-century Germany using letters cast from lead provided a catalyst for increased literacy and the scientific revolution. Automated typesetting machines, such as the Linotype invented in the nineteenth century, changed the way information was produced, distributed, and consumed. In the digital era, the way we consume text has changed drastically since the proliferation of personal computers in the 1980s and the rapid growth of the Internet in the 1990s. Text from emails, websites, and instant messages fill computer screens, and while many of the typographic rules of the past apply, type on screen requires additional considerations for enhanced communication and legibility.

Letters on screen are created by setting the color of pixels. The quality of the typography is constrained by the resolution of the screen. Because, historically, screens have a low resolution in comparison to paper, techniques have been developed to enhance the appearance of type on screen. The fonts on the earliest Apple Macintosh computers comprised small bitmap images created at specific sizes like 10, 12, and 24 points. Using this technology, a variation of each font was designed for each size of a particular typeface. For example, the character A in the San Francisco typeface used a different image to display the character at size 12 and 18. When the LaserWriter printer was introduced in 1985, Postscript technology defined fonts with a mathematical description of each character's outline. This allowed type on screen to scale to large sizes and still look smooth. Apple and Microsoft later developed TrueType, another outline font format. More recently, these technologies were merged into the OpenType format. In the meantime, methods to smooth text on screen were introduced. These anti-aliasing techniques use gray pixels at the edge of characters to compensate for low screen resolution.

The proliferation of personal computers in the mid-1980s spawned a period of rapid typographic experimentation. Digital typefaces are software, and the old rules of metal and photo type no longer apply. The Dutch typographers known as LettError explain, “The industrial methods of producing typography meant that all letters had to be identical… Typography is now produced with sophisticated equipment that doesn't impose such rules. The only limitations are in our expectations.”1 LettError expanded the possibilities of typography with their typeface Beowolf (p. 131). It printed every letter differently so that each time an A is printed, for example, it will have a different shape. During this time, typographers such as Zuzana Licko and Barry Deck created innovative typefaces with the assistance of new software tools. The flexibility of software has enabled extensive font revivals and historic homages such as Adobe Garamond from Robert Slimbach and The Proteus Project from Jonathan Hoefler. Typographic nuances such as ligatures—connections between letter pairs such as fi and æ—made impractical by modern mechanized typography are flourishing again through software font tools.

Draw text

The text() function is used to draw letters, words, and paragraphs to the screen. In the simplest use, the first parameter can be a String, char, int, or float. The second and third parameters set the position of the text. By default, the second parameter defines the distance from the left edge of the window; the third parameter defines the distance from the text's baseline to the top of the window. The textSize() function defines the size the letters will draw in units of pixels. The number used to define the text size will not be the precise height of each letter, the difference depends on the design of each font. For instance, the statement textSize(30); won't necessarily draw a capital H at 30 pixels high. The fill() function controls the color and transparency of text. This function affects text the same way it affects shapes such as rect() and ellipse(), but text is not affected by stroke().

fill(0);

text("LAX", 0, 40); // Write "LAX" at coordinate (0,40)

text("AMS", 0, 70); // Write "AMS" at coordinate (0,70)

text("FRA", 0, 100); // Write "FRA" at coordinate (0,100)

textSize(32); // Set text size to 32

fill(0);

text("LAX", 0, 40);

text("ORD", 0, 70);

text("DAY", 0, 100);

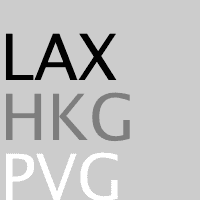

textSize(32);

fill(0); // Fill color black

text("LAX", 0, 40);

fill(126); // Fill color gray

text("HKG", 0, 70);

fill(255); // Fill color white

text("PVG", 0, 100);

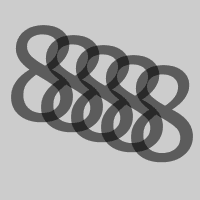

textSize(64);

fill(0, 140); // Fill black with low opacity

text("8", 0, 60);

text("8", 15, 65);

text("8", 30, 70);

text("8", 45, 75);

text("8", 60, 80);

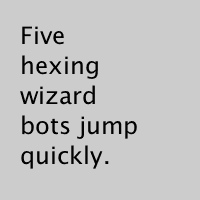

Another version of text() draws the characters inside a rectangle. In this use, the second and third parameters define the position of the upper-left corner of the box and fourth and fifth parameters define the width and height of the box. If the length of the text exceeds the dimensions of the defined box, the text will not display.

String s = "Five hexing wizard bots jump quickly.";

fill(0);

text(s, 10, 10, 60, 80);

String s = "Five hexing wizard bots jump quickly.";

fill(0);

text(s, 10, 10, 60, 55); // Box too small

The examples in this chapter are the first to load external media into a sketch. Up to now, all examples have used only graphics generated within Processing through drawing functions such as line() and ellipse(). Processing is capable of loading and displaying other media, including fonts, images, vector files, formatted data, and sounds. While this chapter focuses on loading fonts and other chapters discuss specific information about other media types, there are a few things about loading media that apply to all categories. These similarities are discussed here.

Before external media can be used in a Processing sketch, it needs to be loaded each time the program is run. Media can be loaded directly from a sketch's folder, another location on the computer, or though the Internet. Most typically, the media is loaded directly from the sketch's folder. Media is usually placed into a folder called data; there are three ways to get media into this folder:

- Add the file by selecting the “Add File” option in the Sketch menu of the Processing environment. Navigate to the file's location on your computer, select the file's icon or name, and click “Open” to add it to the sketch's data folder.

- A file (or group of files) can be dragged and dropped into the Processing text area. If successful, a note will appear in the message area stating, for instance, “One file added to the sketch.”

- Files can be added manually by opening the sketch folder by selecting the “Show Sketch Folder” option from the Sketch menu. Create a folder inside called data if it doesn't exist and copy the file (or files) into that folder.

To confirm the file was added correctly, select “Show Sketch Folder” from the Sketch menu. The file will be inside the data folder. With the image file in the right place, it's ready to load. Be sure to include the file format extension as a part of the name and to put the entire name in quotes (e.g., "pup.gif", "kat.jpg", "ignatz.png") arch.JPG will create an error. Also, avoid the use of spaces in file names, which can cause problems.

To make media files accessible from anywhere in a program, they are typically declared as globally available variables outside of setup() and draw(). Files are usually loaded inside setup() because they need only be loaded once and because it takes time to load them. Loading a file inside draw() reduces the frame rate of a program because it causes the file to reload each frame. Once a file is loaded in setup(), it may be utilized anywhere in the program. In most Processing programs, all files are loaded when the program starts.

Vector Fonts

To work with fonts different than the default, more functions are needed to prepare a font to be used with Processing. The createFont() function is used to convert a TrueType font (.ttf) or OpenType font (.otf) so that it can display through text(). The textFont() function is used to define the current font to display. Any compatible font installed on the computer running Processing or stored in the sketch's data folder may be used. The following short program is used to print the list of the available installed fonts to the console:

String[] fontList = PFont.list();

printArray(fontList);

The printArray() function (p. 420) is used to write each font on a new line. The first few options printed to the console are general typographic classifications such as Serif, SansSerif, and Monospaced. Use these options to define a style, but not a specific font. When the list is generated on the computer used to write this book, a list of 573 font options are printed to the console. Your computer will produce different results depending on the operating system and custom fonts installed. The list starts with general font categories that will work across platforms, then continues with specific font names. A short excerpt from our list follows:

[0] "Serif"

[1] "SansSerif"

[2] "Monospaced"

[3] "Dialog"

[4] "DialogInput"

[5] "ACaslonPro-Bold"

…

[567] "ZXX-Sans"

[568] "ZXX-Xed"

[569] "ZapfDingbatsITC"

[570] "Zapfino"

[571] "Ziggurat-Black"

[572] "Ziggurat-BlackItalic"

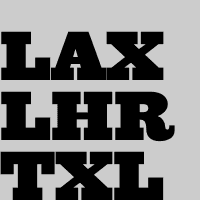

Before a font is used in a program, it must be converted and set as the current font. Processing has a unique data type called PFont to store font data. Make a new variable of the type PFont and use the createFont() function to convert the font. The first parameter to createFont() is the name of the font to convert and the second parameter defines the base size of the font. (Optional third and fourth parameters are defined in the Reference.) The textFont() function must then be used to set the current font. On our development computer, to work with Ziggurat Black, list option 571 above, the following code is run:

PFont zigBlack;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

zigBlack = createFont("Ziggurat-Black", 32);

textFont(zigBlack);

fill(0);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

text("LAX", 0, 40);

text("LHR", 0, 70);

text("TXL", 0, 100);

}

To make this program work on your computer, you will likely need to modify line 5 to work with a font on your machine. This program is similar to code 12-01, but notice the differences in the letters in the Ziggurat font in relation to the default font.

To ensure a font will load on all computers, regardless if the font is installed, add the file to the sketch's data folder. (Fonts in the data folder don't print in the console list as demonstrated in code 12-07.) Follow the instructions on page 10 to add a font to the data folder. When fonts inside the data folder are used, the complete file name, including the data type extension, needs to be written as the parameter to createFont(). The following example is similar to the prior example, but it uses an OpenType font inside the data folder. It uses Source Code Pro, an open source typeface that can be found online and downloaded through a web browser.

PFont sourceLight;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

sourceLight = createFont("SourceCodePro-Light.otf", 34);

textFont(sourceLight);

fill(0);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

text("LAX", 0, 40);

text("LHR", 0, 70);

text("TXL", 0, 100);

}

To use two fonts in one program, create two PFont variables and use the textFont() function to change the current font. Based on the prior two examples, the Ziggurat-Black font loads from its location on the local computer and Source Code Pro loads from the data folder.

PFont zigBlack, sourceLight;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

zigBlack = createFont("Ziggurat-Black", 24);

sourceLight = createFont("SourceCodePro-Light.otf", 34);

fill(0);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

textFont(zigBlack);

text("LAX", 0, 40);

textFont(sourceLight);

text("LHR", 0, 70);

textFont(zigBlack);

text("TXL", 0, 100);

}

Pixel fonts

Processing can also work with fonts that it converts into small image textures. These fonts aren't as flexible and crisp as fonts converted for Processing with createFont() and used with the default renderer, but they are more optimized for use with the P2D and P3D renderers. The difference between renderers is discussed on page 547. The pixel font format used by Processing was developed at the MIT Media Lab in the mid 1990s in the Visual Language Workshop (VLW). The VLW format stores each alphanumeric character as a grid of pixels. It is a quick way to render text and makes it possible to include a font with a sketch without including the vector data.

To convert a font to the VLW format, select the “Create Font” option from the Tools menu. A window opens and displays the names of the fonts installed on your computer that are compatible. Select a font from the list and click “OK.” The font is generated and copied into the current sketch's data folder. To make sure the font is there, click on the Sketch menu and select “Show Sketch Folder.” The Create Font tool offers the option to set the size of the font and to select whether it will have smooth, antialiased edges. This tool also offers the option to export “All Characters,” which means every character in the font will be included and will therefore increase the file size.

The following example uses the same font as the prior createFont() example. The only difference is the replacement of that function with loadFont(). To run these examples, first use the “Create Font” tool to turn a font into a VLW file. Change the name of the parameter to loadFont() to match the name of the VLW file created.

PFont zigBlack;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

zigBlack = loadFont("Ziggurat-Black-32.vlw");

textFont(zigBlack);

fill(0);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

text("LAX", 0, 40);

text("LHR", 0, 70);

text("TXL", 0, 100);

}

When the font is drawn at a different size from the size at which it was created, it is scaled and therefore does not always look as crisp and smooth. For example, if a font is created at 12 pixels and is displayed at 96 pixels, it will appear blurry.

PFont zigBlack;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

zigBlack = loadFont("Ziggurat-Black-12.vlw");

textFont(zigBlack);

fill(0);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

textSize(12);

text("A", 20, 20);

textSize(96);

text("A", 20, 90);

}

For the best results, draw a font at the size at which it was created. If the same font needs to be used at multiple sizes, consider rendering and loading it at these precise sizes. When VLW fonts are used in 3D, letters with different z-coordinates can sometimes occlude other letters. This can be corrected with a hint, see page 547.

Text attributes

Processing includes functions to control the leading (the spacing between lines of text) and alignment. Processing can also calculate the width of any character or group of characters, a useful technique for arranging shapes and typographic elements.

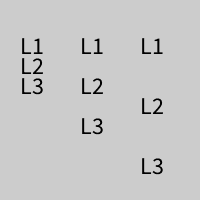

The textLeading() function sets the spacing between lines of text. It has one parameter that defines this space in units of pixels.

String lines = "L1 L2 L3";

textSize(12);

fill(0);

textLeading(10);

text(lines, 10, 15, 30, 100);

textLeading(20);

text(lines, 40, 15, 30, 100);

textLeading(30);

text(lines, 70, 15, 30, 100);

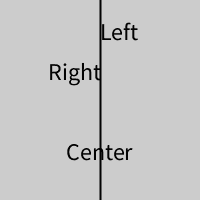

Letters and words can be drawn from their center, left, and right edges. The textAlign() function sets the alignment for drawing text through its parameter, which can be LEFT, CENTER, or RIGHT. It sets the display characteristics of the letters in relation to the x-coordinate stated in the text() function.

fill(0);

textSize(12);

line(50, 0, 50, 100);

textAlign(LEFT);

text("Left", 50, 20);

textAlign(RIGHT);

text("Right", 50, 40);

textAlign(CENTER);

text("Center", 50, 80);

The settings for textSize(), textLeading(), and textAlign() will be used for all subsequent calls to the text() function. However, note that the textSize() function will reset the text leading, and the textFont() function will reset both the size and the leading.

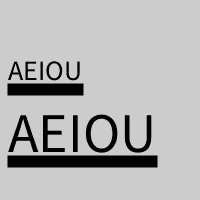

The textWidth() function calculates and returns the pixel width of any character or text string. This number is calculated from the current font and size as defined by the textFont() and textSize() functions. Because the letters of every font are a different size and letters within many fonts have different widths, this function is the only way to know how wide a string or character is when displayed on screen. For this reason, always use textWidth() to position elements relative to text, rather than hard-coding them into your program.

String s = "AEIOU";

float tw; // Text width

fill(0);

textSize(14);

tw = textWidth(s);

text(s, 4, 40);

rect(4, 42, tw, 5);

textSize(28);

tw = textWidth(s);

text(s, 4, 76);

rect(4, 78, tw, 5);

Typing

Drawing letters to the screen becomes more engaging when used in combination with the keyboard. The keyPressed() event function introduced on page 97 can be used to record each letter as it is typed. The following two examples use this function to read and analyze input from the keyboard by using the String methods introduced in the Text chapter (p. 143). In both, the String variable letters starts empty. Each key typed is added to the end of the string. The first example displays the string as it grows as keys are pressed and removes letters from the end when backspace is pressed. The second example builds on the first—when the Return or Enter key is pressed, the program checks if the word “gray” or “black” was typed. If one of these words was input, the background changes to that value.

String letters = "";

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

stroke(255);

fill(0);

textSize(16);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

float cursorPosition = textWidth(letters);

line(cursorPosition, 0, cursorPosition, 100);

text(letters, 0, 50);

}

void keyPressed() {

if (key == BACKSPACE) {

if (letters.length() > 0) {

letters = letters.substring(0, letters.length()-1);

}

} else if (textWidth(letters+key) < width) {

letters = letters + key;

}

}

String letters = "";

int back = 102;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

textSize(16);

textAlign(CENTER);

}

void draw() {

background(back);

text(letters, 50, 50);

}

void keyPressed() {

if ((key == ENTER) || (key == RETURN)) {

letters = letters.toLowerCase();

println(letters); // Print to console to see input

if (letters.equals("black")) {

back = 0;

} else if (letters.equals("gray")) {

back = 204;

}

letters = ""; // Clear the variable

} else if ((key > 31) && (key != CODED)) {

// If the key is alphanumeric, add it to the String

letters = letters + key;

}

}

Many people spend hours a day inputting letters into computers, but this action is very constrained. What features could be added to a text editor to make it more responsive to the typist? For example, the speed of typing could decrease the size of the letters, or a long pause in typing could add many spaces, mimicking a person's pause while speaking. What if the keyboard could register how hard a person is typing (the way a piano plays a soft note when a key is pressed gently) and could automatically assign attributes such as italics for soft presses and bold for forceful presses? These analogies suggest how conservatively current software treats typography and typing.

Many artists and designers are fascinated with type and have created unique ways of exploring letterforms with the mouse, keyboard, and more exotic input devices. A minimal yet engaging example is John Maeda's Type, Tap, Write software, created in 1998 as homage to manual typewriters. This software uses the keyboard as the input to a black-and-white screen representation of a keyboard. Pressing the number keys cause the software to cycle through different modes, each revealing a playful interpretation of keyboard data. In Jeffrey Shaw and Dirk Groeneveld's The Legible City (1989–91), buildings are replaced with three-dimensional letters to create a city of typography that conforms to the streets of a real place. In the Manhattan version, for instance, texts from the mayor, a taxi driver, and Frank Lloyd Wright comprise the city. The image is presented on a projection screen, and the user navigates by pedaling and steering a stationary bicycle situated in front of the projected image. Projects such as these demonstrate that software presents an extraordinary opportunity to extend the way we read and write.

Typographic elements can be assigned behaviors that define a personality in relation to the mouse or keyboard. A word can express aggression by moving quickly toward the mouse, or moving away slowly can express timidity. The following examples demonstrate basic applications of this area. In the first, the word avoid stays away from the mouse because its position is set to the inverse of the cursor position. In the second, the word tickle jitters when the cursor hovers over its position.

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

textSize(24);

textAlign(CENTER);

}

void draw() {

background(204);

text("avoid", width-mouseX, height-mouseY);

}

float x = 33;

float y = 60;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

textSize(24);

noStroke();

}

void draw() {

fill(204, 120);

rect(0, 0, width, height);

fill(0);

// If cursor is over the text, change the position

if ((mouseX >= x) && (mouseX <= x+55) &&

(mouseY >= y-24) && (mouseY <= y)) {

x += random(-2, 2);

y += random(-2, 2);

}

text("tickle", x, y);

}

Notes

- Ellen Lupton, Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Editors, & Students (Princeton Architectural Press, 2004), p. 29.↩